Caracoles

Como sobreviven los Caracoles?

2024-25

work in Progress

COMO SOBREVIVEN LOS CARACOLES (How Snails Survive)

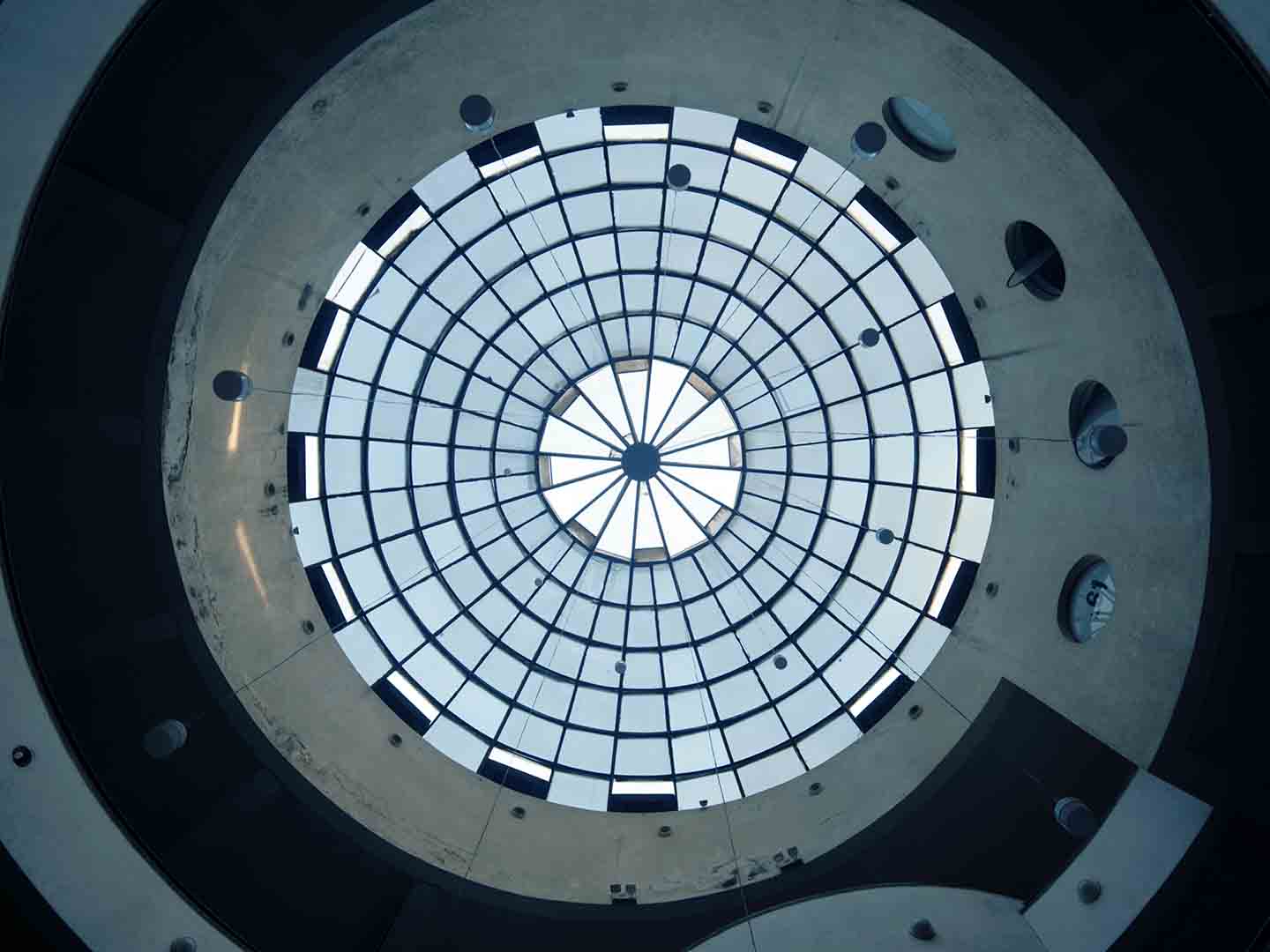

In Chile, a unique architectural phenomenon exists: over 40 snail-shaped shopping centers known as “Caracoles,” inspired by New York’s Guggenheim Museum. Once symbols of modernity, these structures now stand largely forgotten, offering a window into Chile’s evolving society.

This documentary explores how these bygone architectural marvels reflect Chile’s current social landscape, from the utopian ideals of the Allende era to the neoliberal experiments of the Pinochet regime. The film’s cinematography alternates between sweeping architectural shots, showcasing the spiraling structures and a verité-style approach, to document the daily lives of diverse characters within these spaces: recent immigrants, aging Chileans, entrepreneurs, fortune-tellers and -seekers tell their own stories

Los Leones – Santiago, business district – Señora Patricia, the building administrator, ascends the spiraling ramp, distributing monthly utility bills. Most doors, remain silent to her knock, prompting her to slide the bills underneath. Some hairdressers, an accountant, and a pedicurist, open their doors and she hands theirs over and chats away. A food delivery cyclist pushes his bike past her, to the “virtual restaurant” kitchen on the ground floor. Behind several glass doors, unopened letters litter the floors, with for-rent or -sale signs. At the second-last door of the upward walkway, Amaro runs his Harry Potter-themed store. “Here I am with your bad news,” she hands him the papers. “You’re two months late on the bills. If you don’t pay by next week, we’ll have to cut your power.” Amaro, a historian-turned-magician-graphic-designer, prints self-“designed” Harry Potter merchandise. “Lately sales aren’t great,” he admits. “People love my designs, but only customers who look me up make it here.” When Amaro moved in, he researched the building’s history and organized a photo exhibit. The architecture of Chile’s first Caracol pays homage to Wright’s design. Construction began during Allende’s government but was halted by the 1973 coup. It opened a year later, to symbolize the dictatorship’s economic strength. On the slanted, spiraling roof, Amaro looks to the glass monolith of the Costanera Center – South America’s tallest building and the country’s largest, newest, and most luxurious mall, across the street. “People care most about trends, they’re eager for the next new thing. But how can we move on if we don’t even recognize our recent past, what is still here, even if connected to painful memories.” In his workshop, he returns to his designs. They all use logos and graphics he downloads online into his own versions of hats, pins, notebooks, card decks or anything else he can come up with. “Something I have in common with my clients is, I think all of us who are into fantasy really are escaping from some pain in our real lives.” separating Gryffindor and Ravenclaw prints with a boxcutter. “With the exhibit I did want to shine some light on this piece of history. But I had to let go. For now, i have to focus on getting some sales in, I owe both the utilities, and last month’s rent.”

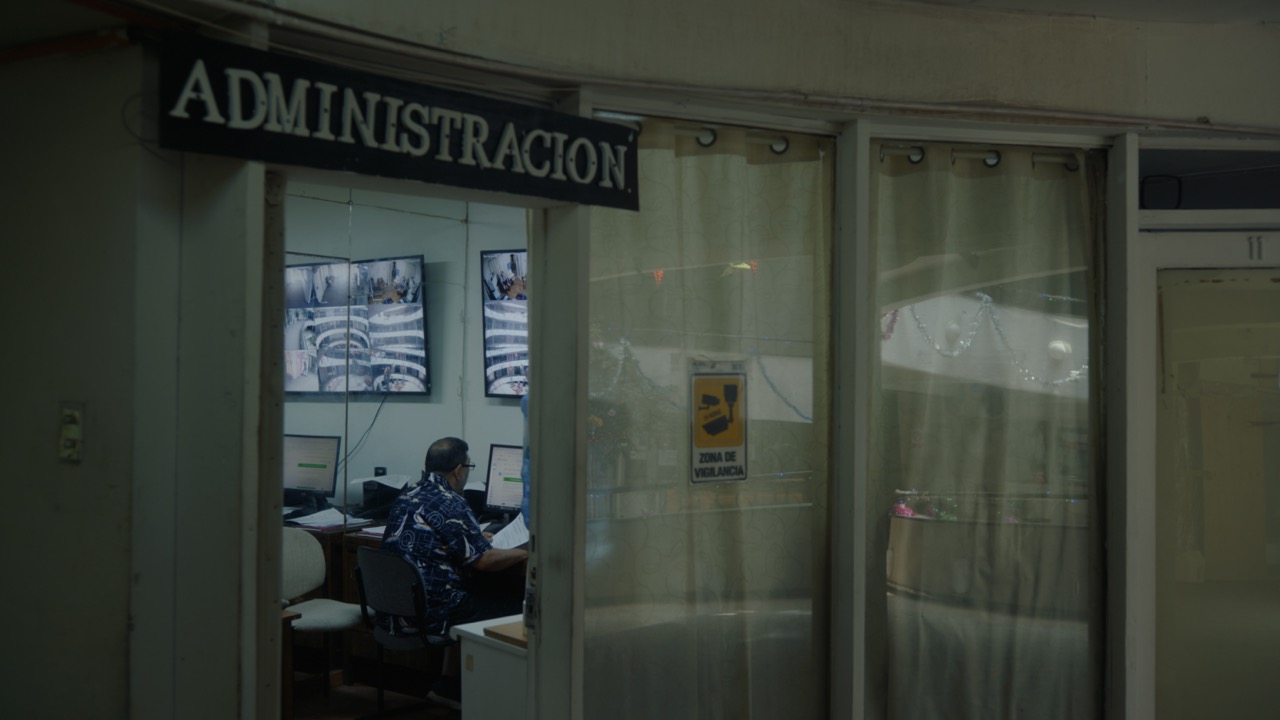

A week later, we meet Señora Patricia, 76, again in her office, smoking at her desk. Together with her husband, Don Luis, 68, she’s been managing the Caracol for nearly 20 years. Amaro paid in time. In the utilities room, Luis checks the numbers of the seven stalls still owing fees. “Just like a movie villain,” he jokes as he flips their switches one by one. “We’re the ones keeping this ‘snail’ alive,” he says. “If it weren’t for us, the owners and renters would have killed it by now— Not long ago, everything was clogged, so we redid all the sewage.” In a yellow rubber suit, boots, and gloves, he descends a ladder to clean the building’s drainage system with a pressure washer. “Our means might be poor, but we make it survive. We know this historical structure inside out, we treat it like our own child.” They arrive early and often stay late. In the evening their office becomes a meeting spot, where they pass their time with the nightguards or handymen who come and stay. Reviewing CCTV footage, as if it were a true crime show. An expensive dog was stolen, they, comment, laugh. “Everyone is a suspect!” Luis cries out, while watching and cracking open a beer.

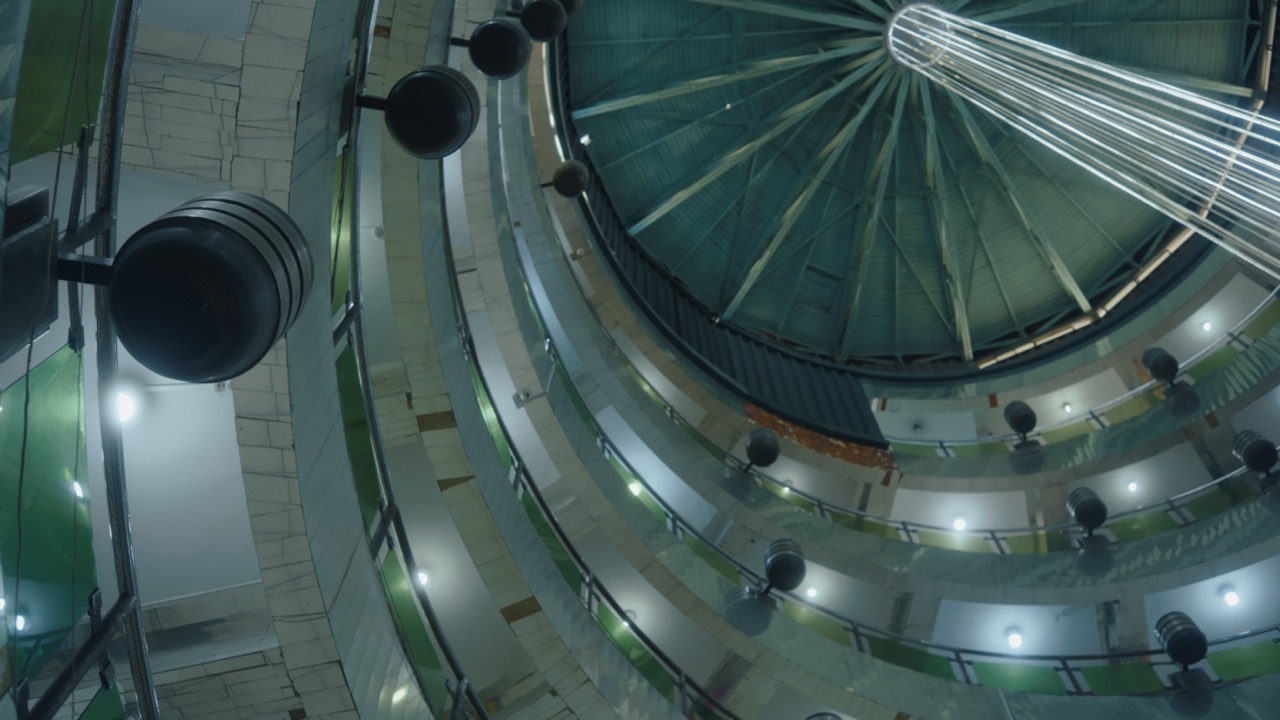

Tres Palacios – Valparaiso – An impressive indoor spiral, fully clad with mirrors, now a futuristic vision left to decay. Of its 120 stores, more than 80 are hairdressers, barbers, and beauty salons. Slot machines hum at the bottom, while a sex shop occupies the very top.

Diego grew up here, gaming and gambling downstairs as a child while his mom worked as a hairdresser. She now owns two salons on the fifth floor – or rather, the fifth bend of the 12-storey circular ramp. “I didn’t really want to become a hairdresser myself,” Diego admits, “but it’s quick money and helps keep my mom’s second salon afloat,”

In recent years, the demographics of Tres Palacios have shifted dramatically. Diego, his mother, and Ivan are now among the few Chileans left working here. Most other barbers, hairdressers, and stylists are immigrants from Venezuela, Colombia, and the Dominican Republic. They brought with them a culture with a stronger emphasis on personal grooming and polished appearances. Combined with the longer hours they work for lower wages, they now have largely overtaken their Chilean counterparts in the Caracol. Today, most clients seek out these immigrant specialists for their grooming needs.

In a country often described as the world’s most neoliberal, everyone seems to be an entrepreneur. Today, most barbers and hairdressers—whether long-established or newly arrived—aren’t employees but “rent a chair” at a salon – where they run their own micro-businesses. ”Everyone in the caracol aspires to move upwards, to climb the spiral of success,” Diego concludes.

Ivan, one of the remaining Chilean hairdressers, observes the busy immigrant-run shops surrounding him. “Look at all these narcos,” he mutters, “They come to get their hair cut every week, with those flashy styles, lines shaved in, and all.” While his immigrant neighbors work non-stop, with queues forming outside their shops, he spends most of his time waiting for his loyal old customers to make appointments. In between, he scrolls through facebook, reads tabloids, and smokes in the back of his salon. “Everything’s gone to hell now. I don’t dare step out after 6 PM—it’s far too dangerous! What this country needs is another coup,” he blurts out. “Like with unruly children; we need a firmer hand. No one knows how to behave anymore. And the police aren’t allowed to do anything about anything!”

“When I was a kid, I felt too ashamed to enter,” another man says entering the mall. “It was so posh, I didn’t dare come in! And look at it now, falling apart!”

Behind one of the few nondescript shop window, an old indigenous lady with failing eyesight reads tarot cards and calls to Pachamama, Mother Earth, offering glimpses into other worlds. “This building is more than 100 years old,” she insists, gesturing at the mirrors. “Just look at them.” Her conviction is unwavering, despite her failing eyesight. “Nearly every porteño has visited this Caracol at least once ,” she continues. “with many regularly coming here for haircuts. This is an important place, just think about the many stories that circulate here”

Bandera – Santiago Centro (Early research) – Called the Caracol de Migrantes by many, it is a place many hesitate to enter, even consider it dangerous, or at least suspicious. It’s busiest on Sundays when immigrant workers have their day off, coming to send Western Union transfers and stock up on foods from their home countries. First, Bolivians and Peruvians established stores here, selling their native condiments and serving dishes. They also set up travel agencies catering to the numerous migrant workers who have come to Chile. Nowadays, they also serve the many who want to move on to the US.

Victoria, a 21-year-old recent arrival from Colombia, now works as a waitress at the Rincón Colombiano. “Of course I knew about this building. before coming. The Caracol was built for us migrants—I’m sure of it!” she exclaims. “It’s famous in Colombia,” she tells me. In the background, TV headlines blare: “Assaulted for $4!”—part of the endless cycle of sensationalist news and crime stories that serve as a backdrop everywhere.